Hagiography: Giovanni Branca

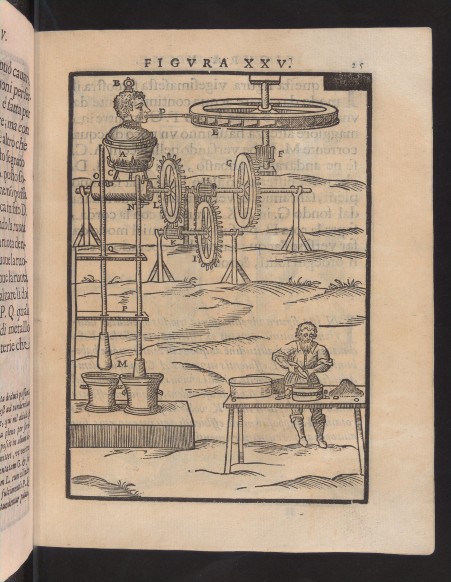

Branca gave the world a different take on the theatrum machinarum genre. Whereas the works of Besson and Ramelli were beautifully engraved and expensive, Branca created an octavo filled with relatively comparatively shoddy woodcuts. Gone are the intricate designs of Ramelli/Bachot and the detailed architectural renderings of Besson/Androuet du Cerceau. As noted by Keller, “Branca’s Le Machine is less rich in material and less beautiful, but not without repute.” (496) Unfortunately, most of Branca’s fame lies in his depiction of what some commentators have taken to be an early steam engine. He deserves more notoriety.

Le Machine is still a very rich source of material. It’s unclear why Branca created the work. His patronage at the Sacra Casa seemed to be secure and the work itself is largely backward looking. The theory for the work seems to emerge from the pseudo-Aristotelian “Mechanical Problems” and notes the work of Heron of Alexandria, as developed by Giovanni Battista della Porta. Unlike earlier authors, Branca doesn’t claim to be the creator of many of the machines and in one instance even expresses some uncertainty over how the machine in question is supposed to function.

The theoretical innocence of the work is somewhat surprising. As evidenced by two extant letters, Branca communicated with Benedetto Castelli and references his work in the last chapter of his architectural manual, a chapter about rivers. Castelli, often considered to be the founder of the field of hydrodynamics, wrote to Branca urging him to defend himself against naïve or interested parties (such as the Venetians who had rejected Castelli’s opinions as to why their lagoons were silting). On another occasion, Branca wrote to Castelli regarding a design for a nozzle for an inverted siphon to be installed in a fountain. Castelli also witnessed the ecclesiastical innocence of Le Machine for the inquisition.

While Branca may have been unaware of new trends in theoretical and methodological approach, Castelli certainly was. He was a personal friend and student of Galileo’s. He became an abbot of the Benedictine monastery in Monte Casino and was appointed as a mathematician to the University of Pisa. One of his students was Evangelista Toricelli, inventor of the barometer and early proponent of the air pump.

Branca’s machine book stands as an interesting mid-point in the spectrum of the genre’s development. As an octavo with woodcuts, it was clearly destines for less well appointed libraries. It also lacks the detail of later works. It does not, for example, contain the measurements provided by Zonca (n.b., Keller also notes that Ramelli didn’t even bother to count teeth in his gearing mechanisms!). According to Keller, his machines “look like armchair inventions which seldom ever had any three-dimensional working counterparts,” (503) although this same complaint could be levelled against other machine works.

It’s unclear how influential Branca’s work was. Hooke owned a copy (and the auction list may even contain a price which could be compared to Besson). Bernini also owned a Branca, an Agricola, and a Ramelli (McGee, 2000)

References

Keller, A.G. (1978). Renaissance Theatres of Machines. Technology and Culture.

McGee, Sarah (2000). Bernini’s Books. The Burlington Magazine. 142.1168: 442-448.

Branca gave the world a different take on the theatrum machinarum genre. Whereas the works of Besson and Ramelli were beautifully engraved and expensive, Branca created an octavo filled with relatively comparatively shoddy woodcuts. Gone are the intricate designs of Ramelli/Bachot and the detailed architectural renderings of Besson/Androuet du Cerceau. As noted by Keller, “Branca’s Le Machine is less rich in material and less beautiful, but not without repute.” (496) Unfortunately, most of Branca’s fame lies in his depiction of what some commentators have taken to be an early steam engine. He deserves more notoriety.

- 1571, 22 April. Branca is born and baptized at San Angelo in Lizzola, Pesaro.

- 1616. He begins employment at the Sacra Casa (Virgin’s Holy House) in Loreto. His work was typical for a Renaissance engineer. He supervised repairs to the structure, designed funeral monuments, and improved fortifications. He also took a role in the local government and acted as a land agent in the administration of the Sacra Casa’s properties. His work also takes him frequently to Assisi and Rome.

- 1622. Made a citizen of Rome.

- 1645, January 24. Branca dies in Loreto.

Le Machine is still a very rich source of material. It’s unclear why Branca created the work. His patronage at the Sacra Casa seemed to be secure and the work itself is largely backward looking. The theory for the work seems to emerge from the pseudo-Aristotelian “Mechanical Problems” and notes the work of Heron of Alexandria, as developed by Giovanni Battista della Porta. Unlike earlier authors, Branca doesn’t claim to be the creator of many of the machines and in one instance even expresses some uncertainty over how the machine in question is supposed to function.

The theoretical innocence of the work is somewhat surprising. As evidenced by two extant letters, Branca communicated with Benedetto Castelli and references his work in the last chapter of his architectural manual, a chapter about rivers. Castelli, often considered to be the founder of the field of hydrodynamics, wrote to Branca urging him to defend himself against naïve or interested parties (such as the Venetians who had rejected Castelli’s opinions as to why their lagoons were silting). On another occasion, Branca wrote to Castelli regarding a design for a nozzle for an inverted siphon to be installed in a fountain. Castelli also witnessed the ecclesiastical innocence of Le Machine for the inquisition.

While Branca may have been unaware of new trends in theoretical and methodological approach, Castelli certainly was. He was a personal friend and student of Galileo’s. He became an abbot of the Benedictine monastery in Monte Casino and was appointed as a mathematician to the University of Pisa. One of his students was Evangelista Toricelli, inventor of the barometer and early proponent of the air pump.

Branca’s machine book stands as an interesting mid-point in the spectrum of the genre’s development. As an octavo with woodcuts, it was clearly destines for less well appointed libraries. It also lacks the detail of later works. It does not, for example, contain the measurements provided by Zonca (n.b., Keller also notes that Ramelli didn’t even bother to count teeth in his gearing mechanisms!). According to Keller, his machines “look like armchair inventions which seldom ever had any three-dimensional working counterparts,” (503) although this same complaint could be levelled against other machine works.

It’s unclear how influential Branca’s work was. Hooke owned a copy (and the auction list may even contain a price which could be compared to Besson). Bernini also owned a Branca, an Agricola, and a Ramelli (McGee, 2000)

References

Keller, A.G. (1978). Renaissance Theatres of Machines. Technology and Culture.

McGee, Sarah (2000). Bernini’s Books. The Burlington Magazine. 142.1168: 442-448.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home